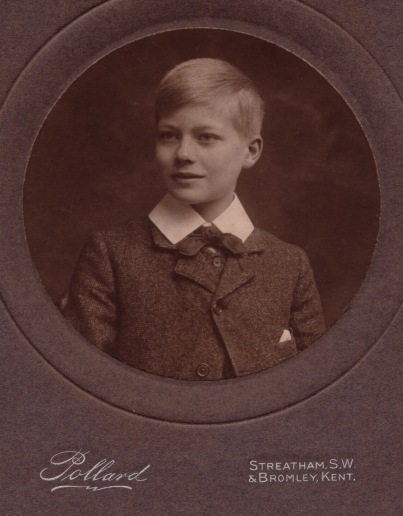

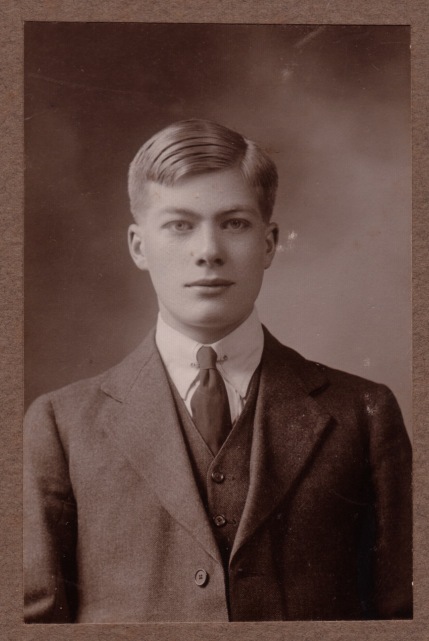

Colin Cullis and J.R.R. Tolkien at Exeter College, Oxford, in 1912 (courtesy of L.L.H. Thompson, R.F. Thompson and H.D.L. Thompson)

‘Not a single man I know is up except Cullis,’ Tolkien lamented at the start of his final year as an Oxford student. It was 1914, war had just broken out, and their friends had left in droves to enlist in the army.

Cullis died one hundred years ago this month – not a victim of war, but as young as many who were. Outside my own books, nothing new has been written about him since Humphrey Carpenter published the snippet above in his 1977 biography of Tolkien. He is not one of the T.C.B.S. – the ‘immortal four’ who play a central role in my Tolkien and the Great War. Yet Cullis was a good friend to Tolkien, and he was one of the few people on hand in that final Oxford year when the Middle-earth legendarium first began taking shape in poetry and Elvish lexicons. A little more about Cullis may be found in my short book Tolkien at Exeter College (including some of the photographs and ephemera mentioned here), but it seems a timely moment to round up, and reflect upon, some of the other material I have gathered about him.

Colin Cullis was born on 28 March 1892 in Streatham, south London, the youngest of eight children (though he lost two siblings before he turned three). His mother Mary was approaching 40.

His father Thomas, secretary of the Surrey Guild commercial dock company, was ambitious for his sons and sent all three to the nearby public (i.e. fee-paying) school. Dulwich College also produced P.G. Wodehouse, inventor of Jeeves and Wooster; C.S. Forester of the swashbuckling Horatio Hornblower novels; and – just before Colin’s arrival – Raymond Chandler, creator of hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe. Here from 1905, Colin excelled in French and, in his final year, edited The Alleynian, the school magazine. He was also a talented photographer, commended for ‘artistic feeling’ in one prize-giving and almost sweeping the board in another. Photographs of Colin himself show him as a golden boy.

In December 1910 he took the Oxford University entrance examination and was accepted by Exeter College to read Classics. The college ratified his £80 scholarship on the same day as Tolkien’s £60 open classical exhibition. Both young men appear in the college’s October 1911 photograph of the new intake.

Cullis, apparently more diligent in Classics than Tolkien, borrowed enthusiastically from the college library – tragedies by Aeschylus and Euripides, comedies by Aristophanes, poetry by Hesiod and Lucretius, oratory by Demosthenes and Cicero, philosophy by Plato, and history by Plutarch. His latter-day borrowings included The World of Homer by Andrew Lang, whose fairy books had fed the imaginations of their generation (including Tolkien); and Cults of the Greek States by Lewis Farnell. This last was a canny choice – Farnell was their classics tutor.

Cullis shared Tolkien’s enthusiasm for William Morris, the towering Victorian artist, poet, author, social polemicist and medieval revivalist. This was the place to follow in Morris’s footsteps – literally. Six decades earlier, Morris had been an Exeter College undergraduate himself. Here he had met Edward Burne-Jones and forged a friendship that laid the foundations of both Pre-Raphaelitism and the Arts and Crafts Movement.

From the library, Cullis borrowed books about Morris and by him. There was his poetry debut, The Defence of Guenevere; his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid and (in 1914) his verse epic The Story of Sigurd the Volsung. Arthuriana, the Aeneid and the Volsunga Saga had already made their mark on Tolkien’s imagination. Cullis took out Morris’s translation of the Odyssey of Homer in 1915 – just when his room-mate Tolkien was attempting to reimagine the lost Germanic legend of Eärendel, an Odysseus of the northern oceans.

Tolkien’s desire to recover the lost past chimed with an antiquarian streak in the Cullis family. John Brailsford, Colin’s nephew by a younger sister, would become Keeper of the Department of Prehistoric and Romano-British Antiquities at the British Museum. More extraordinary was Colin’s elder sister, who had studied at Somerville College, Oxford. Born Mildred Augusta in 1883, in 1915 she underwent baptism as Mary Ældrin Cullis. She appears to have called herself Ældrin – apparently a name concocted to sound Anglo-Saxon. I have seen an undated photograph that shows her grasping a spear and dressed as an Amazonian warrior.

Cullis also shared Tolkien’s taste for clubbable conversation – or perhaps exceeded it. Cullis followed him as president of the Apolausticks, an Exeter College club with a literary focus, founded by Tolkien early in 1912. Cullis also became secretary of the college’s Dialectical Society for philosophical debate, president of the Essay Club, and editor of the college’s Stapeldon Magazine.

Like Tolkien, in autumn 1912 he joined the newly revitalised Exeter College Essay Club. The following term, he delivered a paper on John Masefield, the future Poet Laureate, already famous for ‘Sea-Fever’:

I must down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

As Mark Atherton has said, Masefield’s poem calls to mind ‘To the Sea! To the Sea! The white gulls are crying’ in The Lord of the Rings. When Tolkien gave a paper on the Catholic poet Francis Thompson, Cullis admitted he found Thompson’s religious imagery ‘rather overpowering at times’ and preferred ‘the simple poems of childhood’. Tolkien disagreed – to him, the simple poems and the complex ones were like complementary instruments in a great orchestra. It is probably the revival of the Essay Club that led to the demise of the literary-minded Apolausticks. In 1914, Cullis and Tolkien replaced that with a new club, the Chequers, with a more down-to-earth focus on convivial dinners.

Then there was the Stapeldon, the college debating society. Tolkien supported the equally conservative Cullis on motions that ‘This House deplores the signs of degeneracy in the present age’ and ‘The cheap “Cinema” is an engine of social corruption’.‡ Oxford’s first cinema, the Electric Theatre, had opened in 1910 and by the time of this debate (1914) it had acquired five more.

Yet Cullis found this ‘engine of social corruption’ a handy reference point when describing Tolkien’s writing. As Stapeldon secretary in December 1913, Tolkien had written a parodic account of the meeting that elected him president. At the next meeting, Cullis as new secretary read it out – the first public outing for Tolkien’s epic prose – and recorded that ‘the memory and imagination of the House [was] stirred by the cinematographically vivid minutes of the last meeting’.‡

When Cullis took over as Stapeldon president the following term, he was in for an unusually busy time – in June, the college marked its 600th anniversary. It must have been a relief to reach the sexcentenary dinner on 6 June 1914, when his only duties were to act as a steward and to give the formal reply when Tolkien toasted ‘the College Societies’. His and Tolkien’s signatures are on souvenir menus – among those of many who would not live much longer.

For Cullis (as for the world at large) the froth of activity in June 1914 disguised a tragic malaise.

Like Tolkien, he had managed only a 2nd class in Honour Moderations, the mid-course exams in 1913. While Tolkien switched to the English course and found his academic groove, Cullis continued to read Classics. But as he was embarking upon deep study of Greek and Roman history and philosophy, he began to suffer from heart trouble.

When he failed his Divinity Mods – passages for translation from the Greek New Testament – in June 1913 and December 1914, the college blamed ill health. Cullis was excused from the university’s Officer Training Corps. On doctor’s orders, Cullis was excused from living within college for his final year.

So in October 1914, with war now raging, he took rooms with Tolkien at 59 St John Street, a terraced house round the corner from the Ashmolean Museum. In Oxford slang, they called it ‘the Johnner’. Presumably private lodgings were expected to be quieter and calmer, though one wonders if that is how it turned out. When Tolkien said that not a single man was ‘up’ except Cullis, he cannot have been counting friends outside Exeter. Until the end of the year, his T.C.B.S. friend Geoffrey Bache Smith hung on at Corpus Christi College, and Tolkien found others to socialise with too. For him, at least, life at the Johnner was ‘a delicious joy’ compared with college-bound existence.

Central Oxford, 1911, with St John Street top left and Exeter College lower centre (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

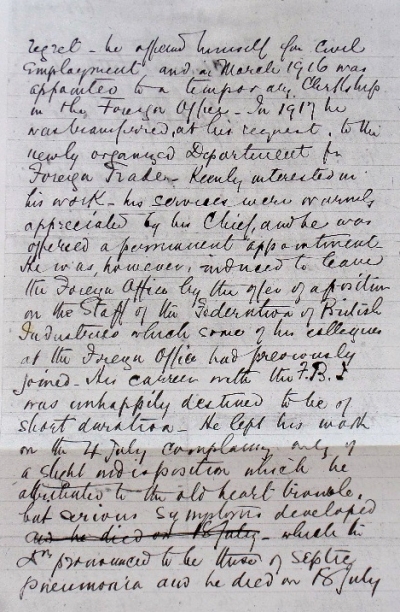

Cullis spent much of the last term away from Oxford, severely ill, and managed only a 3rd class in his final exams in June 1915. Tolkien dashed into the army, but Cullis failed the medical on repeated attempts. That he could not discharge his duty to his country (as three of his siblings did) was ‘to his never-ceasing regret’, in his mother’s words.† His eldest brother Henry took a furlough from the Indian Civil Service, enlisted with the Rifle Brigade, and was killed in action at Armentières, Northern France, in December 1915. Geoffrey, two years older than Colin, served as a captain in the Royal Engineers and then, until 1921, as a Railway Transport Officer in the Balkans. In 1916–17, Ældrin drove field ambulances in Salonika for the Girton and Newnham Hospital Unit, helping Serbian soldiers laid low by malaria and other sicknesses. (Awarded an MBE in 1920, she then vanishes from the record, apart from her arrival in New York in 1940 on the Scythia and her death as a retired tutor in 1968 in Kent, England.)

Colin found work in London as a temporary clerk, in the Foreign Office from March 1915 and in the Department of Foreign Trade from 1916. He showed keen interest and was offered a permanent job, but instead took a staff position at the Federation of British Industries at Crown Office Row, Inner Temple. He cannot have had an easy war. As a man of fighting age who was not doing his military duty, he would have been judged a shirker and coward. And there was his health. He would probably have been better off living with his parents, who had moved to salubrious Boscombe in Bournemouth on the South Coast.

The war ended in November 1918. Tolkien was officially demobilised on 16 July 1919. On Friday 18 July, central London streets began to fill with people securing their places for the huge victory parade the next day. ‘In Trafalgar-square, the Mall, and on the bridges,’ reported The Times, ‘there was not a position offering any possibility of a view … that was not taken by daybreak.’

Cullis, who had been living just six minutes’ walk from Trafalgar Square at 15 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, did not live to see the grand parade. On 4 July, he had left work ‘complaining only of a slight indisposition which he attributed to the old heart trouble’.† It was influenza. By 12 July, he had developed septic pneumonia. Even as his nation began this gathering to celebrate survival, Colin Cullis died at Henrietta Street, aged 27.

Family tradition held that Colin died of Spanish flu, his nephew’s widow Mary Brailsford told me in her old age. It is a natural assumption. In a tremendous recent history of the epidemic, Pale Rider, Laura Spinney calls it ‘the greatest tidal wave of death since the Black Death, perhaps in the whole of human history’, and estimates that in the two years from March 1918 it killed 50 million, possibly even twice that number.

But the ‘tidal wave’ circumnavigated the globe in three waves, and in the northern hemisphere the third is generally considered to have been over by May – two months before Cullis’s death. Laura has kindly given me her verdict: the July date means he is unlikely to have been a Spanish flu victim. Still, it is not cut and dried. ‘A pandemic doesn’t end abruptly,’ says Laura. ‘The pandemic strain just gradually mutates into a more benign form, so asking if he was a victim of the pandemic strain per se or a milder “daughter” strain is a little bit like asking how long is a piece of string. A strain closely resembling the Spanish flu one is still likely to have been his downfall.’

Sources:

Ancestry.com (courtesy of Pat Reynolds); Mark Atherton, There and Back Again: J.R.R. Tolkien and the Origins of The Hobbit (London: I.B. Tauris, 2012); Brailsford family (photographs of Colin Cullis); *Humphrey Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography; †Mary Cullis, handwritten obituary, and other papers from Dulwich College archives (with thanks to Calista Lucy); Colin Cullis’s death certificate; ‡Exeter College archives (with thanks to Penny Baker); London Gazette; E.S. McLaren, A History of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1919); Laura Spinney, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (London: Jonathan Cape, 2017); Stapeldon Magazine (Exeter College); Times Digital Archive.

Reblogged this on A Pilgrim in Narnia and commented:

Once again, John Garth’s careful historical research on WWI and J.R.R. Tolkien and compelling storytelling have produced a beautiful piece. This is the story of Colin Cullis, a friend of J.R.R. Tolkien who survived the war only to pass away 100 years ago this month. For historian buffs or Tolkien fans–or for people who find the stories of everyday people worth hearing about–this is a post worth reading.

Reblogged this on Seasons of Skorn, shadows of the seas: in search of time.

John, you are a wonder!

This is splendid! Thank you very much for all these new, vivid glimpses!

I hope you will indulge the results of my curiosity stirred in a couple directions, when I say, I see that the Cults of the Greek States by Lewis Farnell has been scanned a number of times for the Internet Archive (together with a number of other interesting-looking books by him), and that a not-unreadable microfilm of E.S. McLaren, A History of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1919) is there, too (best read in “Thumbnail view”, greatly magnified). Tangentially to the latter, I heartily recommend Flora Sandes’s An English Woman-Sergeant in the Serbian Army (also from Hodder & Stoughton – in 1916), scanned there, and as a free audiobook at LibriVox.org

Why was the school magazine called The Alleynian, I ask myself – and see, thanks to Wikipedia, how rusty (at best) swathes of my Elizabethan and Jacobean history are, when I read the “Edward Alleyn” article.

Given Colin Cullis’s earlier editorial activities, I wonder if the Federation of British Industries archives at the University of Warwick might have any things of interest (though I suspect you may have pursued that possibility already).

Thank you, as ever, for your interest and feedback. Archive.org is a treasure-house, and I have used it to read (bits of) Cults of the Greek States and Flora Sandes’ memoir. I hadn’t thought of looking at the archives of the Federation of British Industries, but I think I’ll leave that to someone else. I doubt it would yield anything of personal interest about Cullis.

Very interesting! I love these little glimpses into the lives of ordinary people. I am also intrigued by his sister – wouldn’t you love to have had the chance to sit down with her and hear about her life?

Absolutely! – though I believe that dressing up in classical costume for studio photographs was a fad of the era, a long-ago precursor to the cosplay selfie.

Yes, true…but the choice of costume and the name change is intriguing, too. She must have been quite the woman!

I wonder if Andy Orchard would have anything interesting to say about the name ‘Ældrin’? ‘Aldrin’ turned up in my quick search as the surname of a Swede who became a famous American artist, Anders Gustaf Aldrin (1889-1970) – and, his Swedish Wikipedia article tells me, who was also a relative of Buzz Aldrin.

Another wonderful essay. Though she’s peripheral to Tolkien and his friends, I’m fascinated by Mary Aeldrin Cullis — have you visited the Muriel St. Clare Byrne collection at Somerville that holds several of Cullis’s letters? And I’d love to see the costume photograph of her…

No, I didn’t know about that collection. That’s a great spot – thank you! I’ll try to have a look.

Thank you, John Garth, for your your detailed research. Happened across it in April 2021, and wonder at the reflections on the 1918 pandemic as we, hopefully, emerge from our own. I also found a few references to Mary Aeldrin Cullis and her travels including Honolulu to Victoria BC in 1921 and her departure to New York from Liverpool in 1939. Lovely read!

Glad you came here. You’ve prompted me to glance again at my notes on Aeldrin (I have her arriving in NYC on the Scythia, 30 October 1940) and to look up the people she was living with in 1929 at Well Walk, Hampstead.

It was the family of poet Thomas Sturge Moore (brother of philosopher G.E. Moore), including his daughter Riette Sturge Moore (1907–1995), later a successful stage designer. Riette’s obituary in the Independent newspaper says, ‘Outstanding were her designs for St Denis’s version of Kaalevala, the Finnish epic, and the costumes for the Laurence Olivier / Peter Hall Coriolanus in 1959. It was in this Coriolanus that Albert Finney took over from Olivier when understudying and became a star.’ And (perhaps relevant for the presence of Aeldrin in the Moores’ home): ‘Riette Sturge Moore was privately a generous helper, mentor and homegiver to musicians, poets, artists and theatre people like myself who otherwise could never have afforded to have followed their careers.’

Watching The Dig recently about the Sutton Hoo excavation of 1939 (excellent though, of course, flagrantly unhistorical at points), I suddenly heard a familiar name: John Brailsford. He’s one of the minor characters at the dig, and he was the same man I mention in my post – Colin Cullis’s nephew, who became Keeper of the Department of Prehistoric and Romano-British Antiquities at the British Museum. At Sutton Hoo he was only 20 or 21, so I guess he was still a student. It was his widow, Mary (d. 2012), who generously let me look through the family papers and photographs for my biographical research.

How proud Colin would have been, had he lived long enough to see his nephew dig up an Anglo-Saxon ship burial! And you can just picture him thinking, ‘Gosh, I must write to Tolkien about this. He’ll be delighted!’