In which I blow my own trumpet…

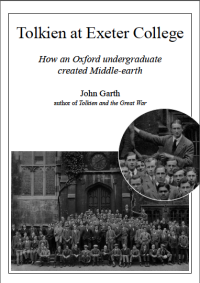

When you picture J.R.R. Tolkien, it’s probably as a member of Oxford’s Inklings, writing The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in the 1930s and ’40s, or in old age when fame caught up with him in the 1960s. Yet he first wrote about Middle-earth in 1914–15 while studying at Exeter College, Oxford University. My 2003 book Tolkien and the Great War started a shift in interest towards the author’s early development. In Tolkien at Exeter College, published by the college in 2014, I return to focus tightly on his undergraduate years.

So how did Tolkien first strike his lifelong creative seam? It’s an unlikely and fascinating tale, involving Beowulf, Hiawatha, the outbreak of war, and – most crucial of all – the college library’s Finnish Grammar. We meet a fresh Tolkien – a classicist who nearly failed Mods; a socialite and slacker who climbed college walls, ‘hijacked’ a bus, and was arrested during a town-versus-gown confrontation. We see his fortunes transformed by an extraordinary sensitivity to language and by a yearning to imagine the dim unrecorded past.

So how did Tolkien first strike his lifelong creative seam? It’s an unlikely and fascinating tale, involving Beowulf, Hiawatha, the outbreak of war, and – most crucial of all – the college library’s Finnish Grammar. We meet a fresh Tolkien – a classicist who nearly failed Mods; a socialite and slacker who climbed college walls, ‘hijacked’ a bus, and was arrested during a town-versus-gown confrontation. We see his fortunes transformed by an extraordinary sensitivity to language and by a yearning to imagine the dim unrecorded past.

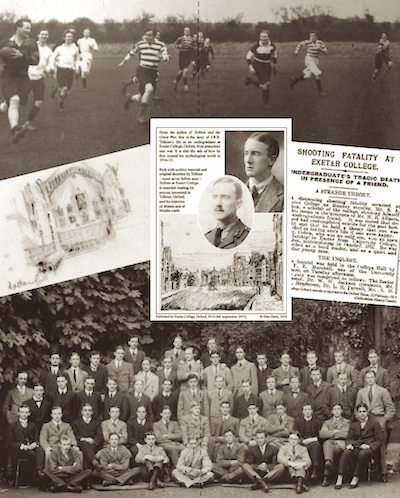

With the help of a series of diverting sidebars, we also see him in context of an Oxford that is both familiar and unfamiliar. There are the student meetings which he recorded in inimitable style as secretary (including one prototypical epic of battle between order and chaos); and the parties and performances he attended. There is a shocking tragedy just a couple of flights of stairs from his room; and the official machinations which allowed him to switch from Classics to English. We meet the friends he gathered in a kind of proto-Inklings, and we follow them into the Great War.

At the same time we trace the invention of ‘Elvish’ and of the first Middle-earth hero, Eärendil the star mariner. And we hear of Tolkien’s return to the college as a Somme veteran to read aloud his first mythological epic of battle.

I first spoke about Tolkien’s Exeter life at a Tolkien conference hosted by the college in 2006. In writing Tolkien at Exeter College, I enjoyed the amazing support of former Rector Frances Cairncross, who invited me to showcase my work at Founder’s Day and in the 2014 City Lecture. It was a delight to to broach Tolkien’s own college memorabilia at the Bodleian Library, and to revisit the college archives with the assistance of archivist Penny Baker and librarian Joanne Bowring. When Sir Peter Jackson came to Oxford to give a lecture in 2015, it was my privilege to show those archives to him and his partner Fran.

By the kindness of the college, the Tolkien Trust, and some hardcore Tolkien collectors, I’ve been able to include in Tolkien at Exeter College a wealth of rare archival images – some previously unseen, including a 1911 matriculation line-up, a photo of Tolkien haring up the rugby pitch, and his own sketches of Exeter College Hall and Broad Street. Matt Baldwin in the Development Office has laid it all out beautifully.

Tolkien at Exeter College: How an Oxford Undergraduate Created Middle-earth (64pp, black-and-white) was a finalist in the prestigious 2015 Mythopoeic Awards for Scholarship (won by Tolkien and the Great War in 2004). Michael Ward, author of Planet Narnia, has described it as ‘a must-read for all Tolkien aficianados’. According to Mythlore, it is ‘a very good thing indeed … belongs on the bookshelf of every Tolkien scholar’. Holly Ordway, in an article on her books of the year, called it ‘an excellent complement’ to Tolkien and the Great War which ‘deepens our understanding of the origins of Tolkien’s lifelong work on The Silmarillion’.

Tolkien at Exeter College: How an Oxford Undergraduate Created Middle-earth (64pp, black-and-white) was a finalist in the prestigious 2015 Mythopoeic Awards for Scholarship (won by Tolkien and the Great War in 2004). Michael Ward, author of Planet Narnia, has described it as ‘a must-read for all Tolkien aficianados’. According to Mythlore, it is ‘a very good thing indeed … belongs on the bookshelf of every Tolkien scholar’. Holly Ordway, in an article on her books of the year, called it ‘an excellent complement’ to Tolkien and the Great War which ‘deepens our understanding of the origins of Tolkien’s lifelong work on The Silmarillion’.

Do you have your copy? Buy it from my website.

This is an updated version of a 2015 article I wrote for Exeter College’s Exon magazine, left.

I would heartily second Holly Ordway’s characterization of it as ‘an excellent complement’ to Tolkien and the Great War – and what a Salmagundi of delight and instruction in its own right, too! And, like Tolkien’s own writing (and that of Lewis and Williams, for that matter) it’s gratifyingly ‘centrifugal’, whetting the readers’ appetites and sending them off eagerly to discover more about things mentioned – such as, for example, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Hiawatha music, in my case (happily available on YouTube thanks to The Longfellow Chorus)!

Thanks, David. I’ve added your comment to my website list of critics’ comments – not least because of that lovely word Salmagundi.

Speaking of “Tolkien haring up the rugby pitch”, I was intrigued to see a recent little ‘complementary’ item on Exeter’s site about Tolkien buying football boots on 11 October 1913!:

http://www.exeter.ox.ac.uk/alumni/news/bodleian-purchases-rare-ledgers-revealing-purchases-tolkien-and-waugh.html

Actually this piece, and others in the wider media, were preceded by a couple I published in my capacity as digital editor of Oxford Today, the University magazine. My colleague Richard Lofthouse first broke the story that Duckers’ was closing in November, and we published some Tolkieniana in a follow-up news item about the sale of the ledgers. I was able to bring in some extra information and imagery from my research on Tolkien at Exeter College (plus, in the headline, a touch of off-kilter humour from my love of Sixties music.)

Thank you – how interesting to see the very entries! (What a sad occasion, though!)

Reblogged this on Skorn and commented:

Got my copy – don’t miss yours!

Pingback: Tolkien at Exeter College « The Spyders of Burslem

In this modern age it is really not surprising that an Old English specialist like yourself resorts to ‘blowing your own trumpet’ so to illustrate how the under-graduate JRR Tolkien created Middle-earth. Particularly given that Gjallarhorn is too tightly in Heimdall’s grip at Bifrost between Midgard and Asgard for academics to make use of so to signal the Ragnarok that could result from people relying too much on movie directors like Peter Jackson and his ensemble of Hollywood actors to portray Middle-earth!

I do not think that many people these days have even got a picture of Tolkien as an inkling writing The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in the 1930s and 1940s, or in old age when fame caught up with him in the 1960s. Let alone a picture of him beginning his Middle-earth legendarium in 1914-15 with the poem that he wrote about Earendil the star mariner inspired by the lines in Crist: ‘eala earendel, engla beorhtast,/ ofer middangeard monnum sended’ (‘hail morning-star, brightest of angels,/ over middle-earth sent to men’)!

Rather the picture that most people these days have of Tolkien is of someone whose works supposedly needed a boost to its readership at the end of the 20th century from Oscar winning movie productions based on those works such as those that Peter Jackson directed. This is while ignoring how the audience from the 80-100 million book sales of The Lord of the Rings that occurred in the near half-century before the production of the movies were announced provided a lot of free publicity to those movies. And now it seems that the special effects that promoted The Hobbit movies, so to justify them being a trilogy, is being employed to promote Mortal Engines, Peter Jackson’s next venture, and movies of similar ilk, which are based on books that do not have the quantity of readership that The Lord of the Rings had even before the production of the movies were announced.

This is despite Christopher Tolkien having works published like his father’s Sigurd and Gudrun, The Fall of Arthur and Beowulf: a translation, during the movies hiatuses to illustrate how Tolkien developed his legendarium, which is interpreted by many fans of the movies merely as the Tolkien Trust cashing in on the movies, as they interpret the Trust’s suing of the movie studios over the franchise attached to both trilogies, which the Trust is doing to stop it. This is with the Trust possibly losing in counter-suing by the studios only the money that it was entitled to in the first place, which it had to sue for, as per the contract that JRR Tolkien signed when he first sold off the film rights, but in the process having stopped the franchise going beyond the limits that the original contract had set.

Fortunately I am protected from such movie fan ignorance by having done a paper at a university here in New Zealand titled: ‘Tolkien and Medieval literature’, in the year after the first Lord of the Rings movie was released. This introduced me to how Tolkien doing his studies in, and teaching of, works such as The Saga of the Volsungs, Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, amongst others, influenced the creation of his legendarium as well as Finnish texts like The Kalevala and an assortment of Welsh texts, amongst others, all which was only enhanced by me doing papers in Old and Middle English and Old Icelandic.

However, the most interesting thing in doing this was attending a lecture at the end of the ‘Tolkien and Medieval literature’ paper, given by a guest lecturer, who I had as a lecturer ten years earlier, who spent the lecture reminiscing about his own under-graduate experience at Oxford in the years that The Lord of the Rings was published. And while this included him talking about his encounters with Tolkien at Oxford and after Oxford, before Tolkien’s death, when he had become a lecturer in Old English like Tolkien, what stood out for me was how my former lecturer and the other young male under-graduates lived like Tolkien in the university colleges in study groups for which was assigned a tutor and a scout, all which is reflected respectively through Frodo and his cousins, Bilbo and Sam.

One of the most interesting things that my former lecturer said about that experience was that despite him being English born, he and his study-mates, who were also English born, were wary of Tolkien thinking that the university made a mistake in appointing him as the Professor of Anglo-Saxon over New Zealand born Kenneth Sisam, a graduate of both Auckland College in New Zealand and Oxford, in a close contest. This is with Tolkien alluding to that closely fought appointment in his valedictory address when retiring from being Professor of English at Oxford to be replaced by New Zealand born Norman Davies, a graduate of both Otago University in New Zealand and Oxford.

As you well know Sisam was also Tolkien’s tutor in Old English even before Tolkien wrote such things as Earendil the star mariner, effectively making him Tolkien’s Bilbo. Tolkien also said of Sisam in a letter that he owed him a debt of gratitude for introducing him to texts that he had never heard of before, which feasibly could have included Crist. This is because in my experience of studying Old English in class we looked at more common texts than Crist like Caedmon’s Hymn, The Battle of Maldon, The Dream of the Rood, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Wulf and Eadwacer, Judith and Beowulf.

Furthermore, my experience of learning Old English et al demonstrated to me how Tolkien’s under-graduate experience at Oxford, not to mention my former lecturer’s experience there, had evolved to the lecturer I had for Old English et al assigning a Bilbo from her honours students to help half-wise Sams like me with our letters, while our lecturer, who did her PhD at Oxford, readied her Frodos for doing PhDs at places like Oxford and Cambridge. And given my lecturer was a woman, as was the Bilbo that she assigned for me and other Sams, who were mainly women like most of the class, as was my lecturer’s last Frodo before she retired, I think Tolkien did very well in having Bilbo teach Sam his letters and then having Sam teach his daughter Elanor her letters! Also, given how my classmates attempted to challenge the university we attended in the midst of it cutting our programme I think that we developed a great understanding of how undergraduates would often get their scout to spy on any meetings between any of their classmates and senior lecturers so that they could also be part of the action. Meanwhile, our tutorials and discussions are something I am reminded of when I read The Lord of the Rings and consider the ‘tutorials’ that the Hobbits have on their way to Mordor, which alas are not reflected in the movies.

Hence, I hope that Tolkien at Exeter College reflects that experience and I hope that it was reflected to Peter Jackson when you showed him Tolkien’s own college memorabilia at the Bodleian Library. Perhaps what is needed now is a bio-pic of Tolkien produced by a movie director who accurately reflects how Tolkien’s under-graduate experiences, his experiences in war, his experiences as a lecturer and an inkling shaped his legendarium, and how this is not understood by those who have since become Tolkien’s fans.

If I may bring another New Zealander into the picture, in the context of “introducing him to texts that he had never heard of before”, or, in this case, introducing any interested reader today both to texts quite new, and texts heard of, but never yet read – or even browsed in – J.A.W. Bennett’s contribution to the Oxford History of English Literature, the volume on Middle English Literature (excluding Chaucer and the drama), which was completed after his death by Douglas Gray and published in 1986, seems a rich source of things Tolkien knew, or probably knew – and taught – or might well have, making one curious what interplay there may have been between various later mediaeval English works and Tolkien’s own fiction.

Thank you for that! Bennett is interesting also for being an Inkling like Tolkien and CS Lewis and succeeding Lewis as Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English at Cambridge University.

Many thanks for this rich and fascinating response. But I must disappoint you: I’m not an Old English specialist, though not a stranger to it either. I studied it briefly as an undergraduate at Oxford, and enjoyed it much more than my peers appeared to do; I’ve since dipped into the language and literature from time to time.

You may well be correct, statistically, about the public perception of Tolkien, simply because so many more people must have seen the movies than have read the books. Still, his readership is vast, and I don’t think the pre-existing popular image of him as an elderly retired don has been quite extinguished. It is indeed deeply and absurdly ironic that Christopher Tolkien’s efforts to make accessible more of his father’s works should be seen as “cashing in” on the movies. Sales may well have risen thanks to the movies – that is economic reality. But sales of Tolkien’s books were high enough already to enable Christopher to devote himself to the long labour of his posthumous editorial work, and I think it is fairly likely that he would have continued as he has, even if the movies had never been made. Putting it another way: without the enormous success of Tolkien’s work during his own lifetime, we would not have The Silmarillion; and if that success had not continued ever since, we would surely have been deprived of all the later publications that have so enriched our understanding of Tolkien’s work. (Such criticism of the Tolkien Trust for seeking profit is partly misguided anyway. Even if it were morally wrong to try to turn your intellectual assets into financial ones – and as a writer I cannot see how that can be the case – a great deal of the Trust’s income is earmarked for charity.)

Who was the lecturer you mention, who had encountered Tolkien in Oxford? I’d love to hear what he had to say.

Your image of the Oxford undergraduate situation is slightly inaccurate.

What you call a “study group” is simply the body of students of the same year studying the same subject at the same college. They study under a tutor based at their own college if it has one, or based elsewhere if it does not. In Tolkien’s case, his college had tutors for him when he was reading Classics, but not when he switched to English. Tutorials, ideally, are one-to-one.

This year/subject-group is not to be confused with the “staircase” system that exists in older colleges such as Exeter that have quadrangles. Rooms for undergraduates are accessed via a number of staircases surrounding the “quad”. Each “staircase” might house half a dozen or so undergraduates. In Tolkien’s day it would have its own “scout” or servant, responsible for cleaning and for serving such meals as were not eaten communally in the college hall.

But yes, both the tutor and the scout resonate in The Lord of the Rings as you say – the tutor in Bilbo, who teaches Frodo, and in Frodo, who teaches Sam, and in Sam, who teaches Elanor; as well as the scout in Sam. It’s also important to note that many of the college scouts went off to become ordinary soldiers in the First World War, and no doubt they made ideal “batmen” or servants. On Sam as Frodo’s batman, see my blog post here.

Kenneth Sisam as Bilbo to Tolkien’s Frodo? Perhaps, but he was not the only one. There had been schoolteachers, and fathers at the Birmingham Oratory, and Tolkien’s own mother. Sisam does stand tall as his Old English tutor, though. And (as far as I can see from what I know about the English syllabus of the day) you’re right to imply that “Crist” was not part of it. However, Sisam taught a course on “English Poetry before the Norman Conquest” which may have been an opportunity for him to explore more widely than the selections in Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader.

Whatever my reservations about the Lord of the Rings movies, and especially about the Hobbit movies, Peter Jackson was charm itself when he visited Exeter College. He and his partner Fran were clearly genuinely thrilled to get a glimpse of Tolkien’s own environment as it was when Middle-earth was first conceived. And he was at pains to stress that his own work was a separate endeavour from Tolkien’s, and that the two must not be confused. In fact, when I told him that some of the movie visualisations had supplanted my much older, personal imagery (Gandalf and Gollum in particular), he told me he thought that was a pity. I wish some of the legions of fan artists who seem to want to recreate the Peter Jackson vision of Middle-earth would have the same attitude!

I would be fascinated to know more both about the English syllabus of the day (indeed, of all of Tolkien’s – and Lewis’s – days) and about lecture lists and such like (where things like Sisam’s course on “English Poetry before the Norman Conquest” are listed). Could you by any chance give a snapshot of how well documented such things are, and how accessible that documentation is, off- or even online?

Thank you MISTER Garth for your response! Rewording the beginning of my original posting: “In this modern age it is really not surprising, but nonetheless very encouraging, that people who have had even a brief experience as an undergraduate studying Old English et al at university and have dipped into the language and literature from time to time since ‘blow their own trumpet’ so to illustrate how the under-graduate JRR Tolkien created Middle-earth”. I am something like that given that I studied Old English et al as a graduate diploma after completing my BA with the paper ‘Tolkien and Medieval literature’ being the last paper I did, while my graduate diploma includes a 400 level paper in Old Icelandic literature, which is the only university paper to date that I have ever done beyond 300 level. And I do blow my own trumpet from time to time but with a tendency to be somewhat stroppy rather than tactful and diplomatic like yourself as you have probably picked up!

This should not be considered surprising given that I live in New Zealand and hence lived through seeing The Lord of the Rings movie production and release being an experience where people like my former lecturer and the lecturer who taught me Old English and other specialists like them residing in this country came into the public arena through newspapers and public lectures and talked about how Tolkien’s speciality influenced the creation of his legendarium. This was before The Hobbit movie production and release became only an experience about what it could do for New Zealand’s film and tourism industries. This is after Old English et al became eroded away from being an essential part of the English programmes in the universities, which was not due to lack of interest, as my lecturer’s retirement party demonstrated with her house bursting at the seams with many of her students who basically had been told that they could simply complete their majors by taking other papers that the English programme had to offer, with that programme having become more and more contemporary since.

This is essentially why I find it encouraging when people like yourself with even your brief experience as an undergraduate studying Old English et al ‘blow your own trumpet’ with works such as Tolkien and the Great War and Tolkien at Exeter College. This is because Tolkien and the Great War clears up the mistaken perception that Tolkien’s legendarium was exclusively created from his war experiences and his professional speciality had nothing to do with it, which the book achieves by firmly placing it in the context of his education prior to and after the war, while it seems Tolkien at Exeter College expands on how his undergraduate experiences contributed to that. And I think that a lot more needs to be said about the latter. Unfortunately it seems that despite the movies including in their extended DVD editions interviews with Tom Shippey, who specialises in Old English, many fans of the movies have not picked up on the language and literature et al that informed Tolkien’s legendarium, which Shippey refers to, and have not seen beyond Tom Shippey’s diplomacy in saying that there are now two ways into Middle-earth: the books written by Tolkien and the movies as interpreted by Peter Jackson. This precludes that language and literature, which is in fact the original way into Middle-earth and is the only way that many of my lecturer’s students have taken, which I have found to be the most enriching going as far as saying to them that they do not need to read the books or see the movies and I envy them for that.

My way into Middle-earth was reading at the age of 11 Astrid Lindgren’s The Brothers Lionheart, described in the blurb as ‘the Swedish Hobbit’, and then setting off with my family from Palmerston North New Zealand, where we lived, over the Manawatu Gorge, which is created by a river flowing east out of some ranges that then get split in two by the river flowing westwards to the sea, imaginatively suggesting to me that it was created by something like the fight between the mountain dragon and river serpent, which the two Lionheart brothers witness in the book. This was then followed by my family on that trip spending a lot of time in the townships of Dannevirke and Norsewood, which are between the gorge and river origins and have street names like Odin Street and Thor Street, and me picking up on how the towns and the country around them were settled by Danish and Norwegian people. This was then followed, in turn, by my brother and I the next day seeing Ralph Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings in the cinema in Masterton, after which, upon returning home, I read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, enjoying the timing of reading the former but not the timing of reading the latter, which was the big drawback in seeing Bakshi’s movie first. Then many years later that time I spent in Dannevirke and Norsewood on that trip and subsequent times I spent at a Catholic monastery nearby since, having many conversations with its resident Caedmon, proved to be a good prelude to studying Old English et al at university.

I totally agree with your assessment about Christopher Tolkien and look forward to the release of Beren and Luthien this month. I find it patently absurd that people are thinking that it is only going to be a release of material already scattered throughout The History of Middle-earth. Such an attitude surely at the very least precludes a lot of new editorial material from Christopher Tolkien being in the edition! I also think that the argument that the increase of book sales, because of the movies, did a lot for Tolkien is something filtered from the movie studios because of what they stand to gain from the royalties in the publishers’ use of cinematographic images on the book covers, which change a lot and lead to a lot of movie fans buying multiple editions of the books.

The name of the former lecturer that I had who encountered Tolkien at Oxford is Robert Neale, who I believe completed his undergraduate studies at Oxford and his post-graduate studies at Michigan University where I believe he taught before going back briefly to Oxford from where he went to Massey University, in Palmerston North, where he taught for thirty years. If you google Robert Neale and Kenneth Sisam you will find part of an article in the Manawatu Evening Standard dated Dec 4 2001 titled ‘There and Back Again’ reported by Ewan Sargent, which coincided with the release of the first Lord of the Rings movies. The article cuts off at Neale saying that many undergraduates felt that Sisam should have been Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford rather than Tolkien and I am not sure how to access the rest of it on line. I have read the full article in the newspaper archives at the National library in Wellington, New Zealand. The last time I saw Neale was when he gave the guest lecture on the ‘Tolkien and Medieval literature’ paper at the end of 2002 and the last I heard of him was at the beginning of 2010 or 2011 in a newspaper article about how he received a New Years’ honour from the Queen. This was for, amongst other things, introducing a writing programme in high schools, which was adapted from a 100 level paper that he taught at Massey, which I did in 1989 that ultimately helped me with my academic writing, which is how he stands tall for me.

My use of terms like Bilbos, Frodos and Sams are not really intended to apply to certain individuals but to reflect a system and how it is portrayed in The Lord of the Rings. However, I note that Tolkien dates Frodo being orphaned at the same age that he himself was orphaned. Then Bilbo adopts Frodo when Frodo is the same age that Tolkien was when he took up Old English with Sisam as his tutor. Then Frodo inherits the Ring from Bilbo at the same age that Tolkien was when he contested Sisam for Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, which is then followed by Frodo and Bilbo departing from the Grey Havens when Frodo is the same age that Tolkien was when he became Professor of English at Oxford. Notably too the unpublished epilogues for The Lord of the Rings, dated at the time Sam and his family meet Aragorn and Arwen at the Brandywine Bridge, is when Frodo would have been 67 if he had of stayed in Middle-earth, which I believe was the same age that professors were expected to retire at Oxford, which is the age when Tolkien retired. Hence perhaps Frodo’s mother represents Tolkien’s mother, while the adventurous Brandybucks and Tooks that Frodo encountered between the ages of 12-21, while residing in Brandyhall, embodied by Rory Brandybuck at Bilbo’s farewell party, could represent Tolkien’s school-teachers and the fathers at Birmingham Oratory. I also note in the letter where Tolkien said that he owed a great debt to Sisam he said that he certainly derived from him much of the benefit which Sisam attributed to Professor Napier’s example and teaching as well as his affection for a great man in his decline. This is perhaps represented in The Lord of the Rings through Bilbo reflecting something of the Old Took to Frodo with the difference being that Bilbo shows more youth and vigour and hence has a good relationship with younger members of his Took family due to the Ring, which perhaps represents how Sisam was only five years older than Tolkien. This is while it seems that Tolkien’s only encounter with Napier could be reflected in the book by Pippin describing Fangorn to be like a room that the Old Took resided in which grew older and shabbier along with him.

I will also add here that James McNeish in his book Dance of the Peacocks speaks of Sisam being the ‘godfather’ of a ‘mafia’ of New Zealanders, which included Jack Bennett and Norman Davis, who infiltrated Oxford in sustaining the teaching of early English language studies there. This is with Phillip Ardern being the progenitor of this ‘mafia’ who after studying Old English at Oxford taught it at Auckland College, with Sisam being one of his pupils and then his assistant. This is perhaps why Tolkien said in his valedictory address in 1959, upon retiring from his professorship, that it seemed just that someone from Australia or New Zealand filled an Oxford English chair because of the contribution that people from both countries had made to the department and perhaps that justice had been delayed since 1925. This refers, I believe, to Norman Davis replacing him after a close contest with Australian Eric Dobson and to his earlier contest with Sisam for the Anglo-Saxon chair. NB McNiesh’s book is mainly about five New Zealanders, James Betrram, Geoffrey Cox, Dan Davin, Ian Milner and John Mulgan, who went to Oxford and about their experiences related to the rise of Hitler and Mao Tse Tung and how that informed their literary contributions to the Oxford University Press when Sisam was running its publishing.

McNeish also said that ‘it is apparently true’ that after Napier died Sisam basically took over the running of the Old English programme at Oxford until Napier was replaced. This reminds me of how after my lecturer, who taught me Old English, retired one of her students who did her PhD at Cambridge was contracted by my university to supervise my lecturer’s MA students to finish their theses. That person was also my tutor for ‘Tolkien and Medieval literature’ eight years earlier and some of us, while she was contracted at the university upon our lecturer’s retirement, used to join her in translation sessions at our retired lecturer’s house, which this person was house-sitting while my lecturer and her husband were away overseas on their retirement holiday. And I can say that she had gained much of the benefit et al that she got from having our lecturer as her teacher like Tolkien said that Sisam got from Napier.

I also can say from that that perhaps Tolkien is conveying in The Lord of the Rings the benefits of such education and how it developed in Oxford because of the contribution that people made from elsewhere there. This includes people since Tolkien like my lecturer when she did her PhD at Oxford following doing her earlier studies in the USA where she was born, after which she taught many years in New Zealand, which was also the case of her husband, who did his PhD at Oxford too specialising in Medieval English like CS Lewis, which he taught many years in New Zealand. Hence such education is not just Oxford-centric.

I have no reason to doubt that Peter Jackson and his partner were charm itself when they visited Exeter College. And I do pick up from the lecture that he gave at the time that he goes to great pains to stress that his own works was a separate endeavour from Tolkien’s etc. especially when claiming to not be one of Tolkien’s biggest fans, or to be a Tolkien expert. I picked this up also from reading Brian Sibley’s Peter Jackson: A Film-makers Journey a few years ago. It seems though this is something that has not filtered through his vast fan base and the legions of fan artists who seem to want to recreate his vision of Middle-earth, just like what Tom Shippey says in his interviews in the DVDs does not filter through them beyond him saying that there are now two ways into Middle-earth: the books written by Tolkien and the movies as interpreted by Peter Jackson. As for any visualisations I had of anyone in Tolkien’s books from any visual adaptions based on them they have been well and truly supplanted by my experiences with those people I learnt Old English et al with and anyone else we encountered throughout that experience. And I wish that more and more people could have that experience too, which is something that I would talk about with Peter Jackson if I ever encountered him.

Thanks for your kind words about Tolkien and the Great War. Yes, I felt it was vital to put Tolkien’s war experiences in the context of his development already – and also, much more interesting. Just yesterday, writing another piece, I came up with what I think is a good image for all this: in Tolkien, the Great War struck an iron blow against a bell forged of older alloys, ancient, classical and medieval.

I’d like to know more about that sort of Australian parallel, too, considering (for a big instance) that Bruce Mitchell was supervised by Tolkien, and stayed on teaching delightfully at Oxford for decades.

Yeah I would like to see a snapshot of the English syllabus, lecture timetable etc in Tolkien’s under-graduate days (including Sisam’s contribution), after he became Professor of Anglo-Saxon and after he became Professor of English Lang and Lit as he put it. I get the impression after Tolkien retired and Lewis died there were quite a few Australians and New Zealanders teaching Old English and Medieval English at Oxford and Cambridge over many years, while in Australian and New Zealand universities Old English and Medieval English were taught by quite a few English graduates of Oxford and Cambridge. Also, Dance oi the Peacocks said that Australians in the English school of Oxford accused the New Zealanders of cronyism and hence Tolkien in his valedictory address was redressing this Trans-Tasman rivalry by being diplomatic in referring to both countries’ people’s contribution to the school as well as referencing his own South African birth.

The most readily available information about Tolkien’s undergraduate syllabus is in the Chronology volume of Christina Scull and Wayne G Hammond’s JRR Tolkien Companion and Guide.

Great, thanks! (Though I had probably better wait for the second ed. which they discussed on their blog in October 2016 as probably being ready by September 2017, than go hunting to buy a second-hand first ed., having never gotten one sooner, when it was still in print!)

Another fascinating scholar and writer at least passing through this picture is Eric Partridge, born in New Zealand, where he “passed the first ten-or-so years in a country district”, “migrated from New Zealand to Australia” at thirteen, a Classicist who “enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force”, who at 22, as “the only ‘Anzac’ left in [his] section […] was persuaded to lead” it into battle, and, crossing No Man’s Land, “stopped one”. On his return to Australia in 1919, he “changed from an honours course in Classics to one in French and English”, and in 1921 “came to England and went to Oxford”. All the preceding snippets of quotation are from his autobiographical book, The Gentle Art of Lexicography as pursued and experienced by an addict (1963). I’d love

[Did something wrong, there!] Partridge, later in the book, noting that “Mr. R.W. Burchfield […] like Professor Norman Davis and myself, is a New Zealander”, observes, “There must, in our small country, be something that leads its native-born males into the fields of language, for, besides the three persons mentioned, one has only to recall the names of Kenneth Sisam, […] Professor Fraser Mackenzie, […] and Dr J.A.W. Bennett”. But I’d love to know more about his interactions, if any, with the Principle Inklings (none of whom appear in the index).

Partridge’s etymological dictionary Origins was a delight to me as a teenager – it was to this I turned after Tolkien’s invented languages awoke my interest in word origins. I think I must have had it on repeat loan from our local library (Camberley in Surrey) for the better part of a couple of years – a record beaten only by The Times Atlas of the World.

Thank you Mr Garth. ‘In Tolkien, the Great War struck an iron blow against a bell forged of older alloys, ancient, classical and medieval’. Yep great image!

I wonder sometimes if Tolkien is referencing himself and his friends individually in the Hobbits. The name Tolkien is related to the old Germanic for ‘fool-hardy’ from which comes the name Took, hence perhaps linking Tolkien to Peregrin Took. The American ‘buck parties’ as opposed to English ’bachelor parties’ might link Geoffrey Bache Smith with Merriadoc Brandybuck. The ‘wise’ element of Christopher Wiseman and Samwise Gamgee’s respective names might link them. Frodo Baggins’ ‘elvish-air’, his saying in the High-elven tongue ‘a star shines on the hour of our meeting’ to Gildor and sailing into the west with Earendil’s star in Galadriel’s phial, which shone in Shelob’s lair, might link Frodo with Rob Gilson, Gildor meaning ‘star-lord’ and hence Gilson meaning ‘star-son’. Also, Frodo’s survival of Shelob’s stinging and Merry being called back from the Black Breath by Aragorn in the Houses of Healing might analogise ‘eucatastrophes’ of Gilson and Smith’s respective deaths.

Meanwhile, on the Napier/Sisam and Old Took/Bilbo link that I suggested, James McNeish in Dance of the Peacocks says of Sisam that the robust and powerfully built New Zealander had been reduced by a mysterious illness to the state of a cripple and was obliged to teach from a couch, confined to his room like an invalid, in 1915-16. This suggests the Hobbits’ meeting Bilbo in his room at Rivendell after returning from their quest, while Tolkien’s one encounter with Napier in a very dim room suggests Pippin describing to Merry Fangorn Forest as being like the old room at the Smials in Tuckborough where the Old Took lived year after year.

It’s certainly true that in his “Lost Tales” notes Tolkien equated himself, Edith, and his brother Hilary with lesser Valar (Noldorin, Erinti and Amillo). The chief evidence for this is abstruse but systematic: Tolkien assigns each of these Valar a calendar period within which the birthdays of the real people sit. These figures never got to play much of a part because their main involvement was in climactic sequences Tolkien did not reach in his writing. It’s also certainly true that real places important to Tolkien were mythologised: Oxford, Warwick, Great Haywood, Withernsea, Gipsy Green. So it would be reasonable (because evidence-based) to think that in the 1910s Tolkien liked to place personal links inside his fiction. Even then, though – and when Gilson and Smith’s deaths were fresh griefs – I have noticed no compelling sign of the TCBS members’ presence.

By the time he was writing The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien had moved a long way from that early conception. It can’t be denied that he may have wanted to capture aspects of real people and places, but arguing convincingly for particular identifications is not easy. Here are a couple of examples of what might be done – and let me make plain that I don’t believe them for a minute. Wiseman’s name is like Saruman, and Wiseman was a man of science, so is Saruman an attack on Wiseman? Tolkien’s middle name was Ronald, often shortened to Ron; when he was in a bad mood he was sour: so is Sauron (pronounced roughly Sour-Ron) a portrait of himself at his worst? Surely no and no. I would like to examine some of the larger questions of personal identification in The Lord of the Rings at length, but this isn’t the place for it.

Tangentially, or perhaps more by way of contrast than comparison, there seem to be some extraordinary bits of name-play (and composite character-friend references) going on in The Notion Club Papers.

I cannot imagine Tolkien hijacking a bus! Wonderful image.

He was clearly using a bit of poetic licence!