Here’s an excerpt from my book Tolkien and the Great War to mark the centenary of Tolkien’s discharge on 9 December 1916 from military hospital, where he had begun writing his first ‘lost tale’ of Middle-earth, ‘The Fall of Gondolin’. He had contracted chronic trench fever in October after nearly four months on the Somme battlefield, where the British secret weapon, the tank, had been unleashed. For an overview of the embryonic mythology as it stood just prior to this point – very different in many details and names from the later Silmarillion – see here.

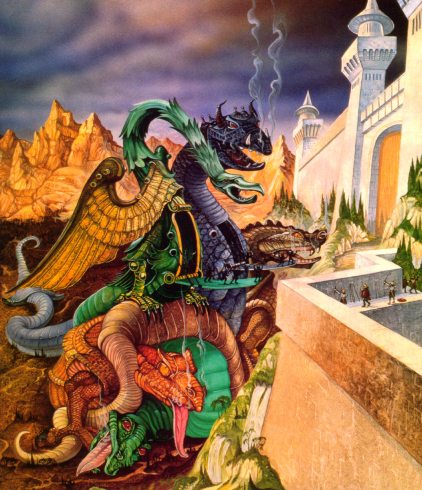

The Fall of Gondolin as depicted by Roger Garland

Tolkien had listed several monstrous creatures in the ‘Poetic and Mythologic Words of Eldarissa’ and its ethnological chart: tauler, tyulqin and sarqin, names which in Qenya indicate tree-like stature or an appetite for flesh. All these new races of monsters proved transitory, bar two: the Balrogs and the Orcs. Orcs were bred in ‘the subterranean heats and slime’ by Melko. ‘Their hearts were of granite and their bodies deformed; foul their faces which smiled not, but their laugh that of the clash of metal….’ The name had been taken from the Old English orc, ‘demon’, but only because it was phonetically suitable. The role of demon properly belongs to Balrogs, whose Goldogrin name means ‘cruel demon’ or ‘demon of anguish’. These are Melko’s flame-wielding shock troops and battlefield captains, the cohorts of Evil.

Orcs and Balrogs, however, are not enough to achieve the destruction of Gondolin. ‘From the greatness of his wealth of metals and his powers of fire’ Melko constructs a host of ‘beasts like snakes and dragons of irresistible might that should overcreep the Encircling Hills and lap that plain and its fair city in flame and death’. The work of ‘smiths and sorcerers’, these forms (in three varieties) violate the boundary between mythical monster and machine, between magic and technology. The bronze dragons in the assault move ponderously and open breaches in the city walls. Fiery versions are thwarted by the smooth, steep incline of Gondolin’s hill. But a third variety, the iron dragons, carry Orcs within and move on ‘iron so cunningly linked that they might flow … around and above all obstacles before them’; they break down the city gates ‘by reason of the exceeding heaviness of their bodies’ and, under bombardment, ‘their hollow bellies clanged … yet it availed not for they might not be broken, and the fires rolled off them’.

The more they differ from the dragons of mythology, however, the more these monsters resemble the tanks of the Somme. One wartime diarist noted with amusement how the newspapers compared these new armoured vehicles with ‘icthyosaurus, jabberwocks, mastodons, Leviathans, boojums, snarks, and other antediluvian and mythical monsters.’ Max Ernst, who was in the German field artillery in 1916, enshrined such comparisons on canvas in his iconic surrealist painting Celebes (1921), an armour-plated, elephantine menace with blank, bestial eyes. The Times trumpeted a German report of this British invention: ‘The monster approached slowly, hobbling, moving from side to side, rocking and pitching, but it came nearer. Nothing obstructed it: a supernatural force seemed to drive it onwards. Someone in the trenches cried, “The devil comes,” and that word ran down the line like lightning. Suddenly tongues of fire licked out of the armoured shine of the iron caterpillar … the English waves of infantry surged up behind the devil’s chariot.’ The war correspondent Philip Gibbs wrote later that the advance of tanks on the Somme was ‘like fairy-tales of war by HG Wells’.

The more they differ from the dragons of mythology, however, the more these monsters resemble the tanks of the Somme. One wartime diarist noted with amusement how the newspapers compared these new armoured vehicles with ‘icthyosaurus, jabberwocks, mastodons, Leviathans, boojums, snarks, and other antediluvian and mythical monsters.’ Max Ernst, who was in the German field artillery in 1916, enshrined such comparisons on canvas in his iconic surrealist painting Celebes (1921), an armour-plated, elephantine menace with blank, bestial eyes. The Times trumpeted a German report of this British invention: ‘The monster approached slowly, hobbling, moving from side to side, rocking and pitching, but it came nearer. Nothing obstructed it: a supernatural force seemed to drive it onwards. Someone in the trenches cried, “The devil comes,” and that word ran down the line like lightning. Suddenly tongues of fire licked out of the armoured shine of the iron caterpillar … the English waves of infantry surged up behind the devil’s chariot.’ The war correspondent Philip Gibbs wrote later that the advance of tanks on the Somme was ‘like fairy-tales of war by HG Wells’.

Indeed, there is a whiff of science fiction about the army attacking Gondolin, a host which has ‘only at that time been seen and shall not again be till the Great End’. In 1916, Tolkien was anticipating the dictum of Arthur C Clarke, ‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.’ From a modern perspective this enemy host appears technological, if futuristic; the ‘hearts and spirits of blazing fire’ of its brazen dragons remind us the internal combustion engine. But to the Noldoli the host seems the product of sorcery. ‘The Fall of Gondolin’, in Tolkien’s grand unfolding design, is a story told by an Elf; and the combustion engine, seen through enchanted eyes, could appear as nothing other than a metal heart filled with flame.

This is so fascinating (and finely contextualized: for which, many thanks)! While there are accounts of mechanical ‘animals’ from antiquity on, I wonder: how unusual – and original – is the imagination of such ‘beasts like snakes and dragons’ – not mere machines, in some sense (seemingly) living organisms, yet some carrying Orcs within, variously like and unlike both the ‘piscem grandem’ of chapter two of Jonah and the Trojan Horse? I wonder, too, if any of these ‘dragons’ may further be possessed of reason and speech, like Glórund (and, later, Smaug)? And, again, whether there is any play, critical and witty, on Tolkien’s part with the Cartesian conception of animals as ‘machines’?

The depth of the connection between the imagery, symbolism and even narrative descriptions in a lot of Tolkien’s writing, and the First World War experience (largely his own, but also others) has unfolded to me not just through your book – which I own and which I enjoyed reading – but also through the intersection between my long-standing enthusiasms for Tolkien and my own academic historical work into that war (my latest book on it was published last week, here in New Zealand, in fact). To me the synergies between Tolkien’s mythos and the First World War are abundantly clear on many, many levels – both at the deeper symbolic level, through to the jealousies surrounding longevity, through to imagery such as the Dead Marshes (trench systems), down to the nature of Orc-talk in The Lord Of The Rings, which was pure Western Front soldier chaff. To me this comparison also highlights another layer of meaning in Tolkien’s work: he drew on the same mythologies as Wagner, by and large, to produce something that was very much the antithesis, politically and otherwise, of Wagner’s. I have to wonder how far that reflected not just the quintessential ‘Englishness’ of Tolkien’s general outlook, but also the lessons he took – morally, particularly – from that war.

Pingback: New JRR Tolkien book 'inspired by Battle of the Somme' to be published this year • Zenit-ka.ru

Regarding Arthur C Clarke’s dictum that “any sufficiently advanced technology looks like magic”: there’s an episode of Doctor Who (Sylvester McCoy era) where the Doctor says that “any sufficiently advanced magic looks like technology”.

Brilliant!

I recently read Louis E. Hagen’s Operation Market Garden memoir, Arnhem Lift: Diary of a Glider Pilot (1945), in Dutch translation and encountered what seemed a sort of partial imaginative analogue of both the tanks at Gondolin and the attacking Ents and Huorns. On Friday, they suddenly saw what seemed ‘a mountain of branches and tree trunks’ on the move, later concluding that this approaching ‘mountain of branches and leaves’, also described as a “monster”, must be a self-propelled gun. I have not managed to compare the English original, but the characterization intrigued me.

I wonder whether the writer knew of Macbeth and Birnam Wood.

I would guess so – though when he might first encounter it is an interesting question (e.g., Schiller translated Macbeth – how popular was it, in German or English, in or out of school?). Another thought which sprang to mind is a possible evocation of some version of what Tolkien discusses in his 5 March 1964 letter to Eileen Elgar (Letter 255) – “the treacherous island that is really a monster”. Louis Hagen’s 13-year-younger compatriot, Michael Ende, has an interesting discussion of turtles in his own work and their mythological sources, not least the mountain that turns out to be the ancient giant turtle, Morla, in The Neverending Story.

I somehow lived this long without being aware that there were ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ tanks (with reference to their armament), but having learned it, I immediately wondered if that might have contributed to the ‘organic’, creaturely imaginations of tanks you note, and perhaps to Tolkien’s imagination in ‘The Fall of Gondolin’ in particular.