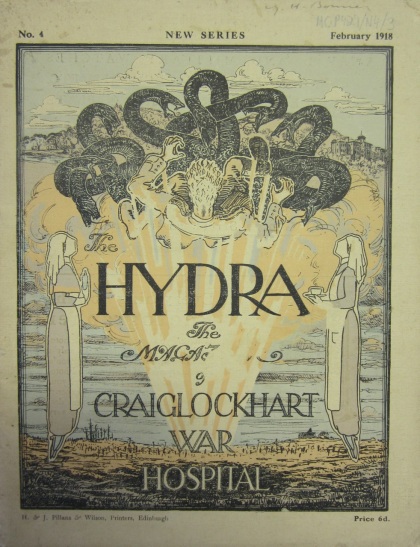

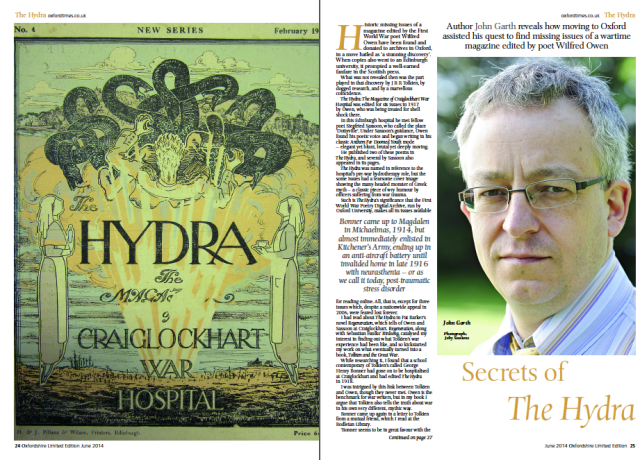

One of the missing issues of The Hydra, rediscovered in an Oxford attic thanks to my researches. The magazine was produced by officers being treated for war trauma. Wilfred Owen published his first classic war poems in its pages.

Historic missing issues of a magazine edited by First World War poet Wilfred Owen have been found and donated to archives in Oxford, in a move hailed as ‘a stunning discovery’. When copies also went to an Edinburgh university, it prompted a well-earned fanfare in the Scottish press. What was not revealed then was the part played in that discovery by J.R.R. Tolkien, by dogged research, and by a marvellous coincidence.

The Hydra: The Magazine of Craiglockhart War Hospital was edited for six issues in 1917 by Owen, who was being treated for shell shock there. In this Edinburgh hospital he met fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon, who called the place ‘Dottyville’. Under Sassoon’s guidance, Owen found his poetic voice and began writing in his classic ‘Anthem For Doomed Youth’ mode – elegant yet blunt, brutal yet deeply moving. He published two of these poems in The Hydra, and several by Sassoon also appeared in its pages.

The Hydra was named in reference to the hospital’s pre-war hydrotherapy role, but some issues had a fearsome cover image showing the many-headed monster of Greek myth – a classic piece of wry humour by officers suffering from war trauma. Such is the Hydra’s significance that the First World War Poetry Digital Archive, run by Oxford University, makes all its issues available for reading online. All, that is, except for three issues which, despite a nationwide appeal in 2006, were feared lost forever.

I had read about the Hydra in Pat Barker’s novel Regeneration, which tells of Owen and Sassoon at Craiglockhart. Regeneration, along with Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong, catalysed my interest in finding out what Tolkien’s war experience had been like, and so kickstarted my work on what eventually turned into a book, Tolkien and the Great War. While researching it, I found that a school contemporary of Tolkien’s called George Henry Bonner had gone on to be hospitalised at Craiglockhart and had edited the Hydra in 1918. I was intrigued by this link between Tolkien and Owen, though they never met. Owen is the benchmark for war writers, but in my book I argue that Tolkien also tells the truth about war in his own very different, mythic way.

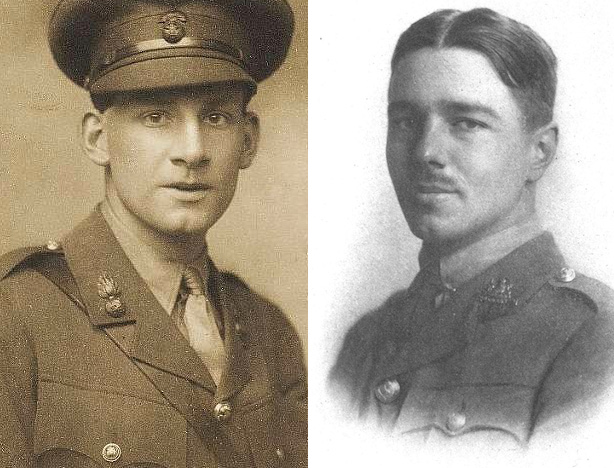

The meeting of Siegfried Sassoon and, right, Wilfred Owen at Craiglockhart had profound effects on Owen’s writing, which came to set the benchmark for war poetry

Bonner came up again in a letter to Tolkien from a mutual friend, which I read at the Bodleian Library. ‘Bonner seems to be in great favour with the B’ham TCBSites,’ the 1913 letter from R.Q. Gilson said. ‘I don’t know whether they propose his admission to the charmed circle.’ The TCBS, or Tea Club and Barrovian Society, was a clique founded by Tolkien at King Edward’s School in Birmingham just before he came up to Oxford in 1911. Initially rather frivolous, on the outbreak of war it suddenly grew up, and its core members became the first to read Tolkien’s earliest ‘Middle-earth’ writings almost exactly 100 years ago.

Bonner was not a core ‘TCBSite’, and indeed may never have been admitted ‘to the charmed circle’. But he went on to a post-war career in journalism, and it struck me that if anyone was likely to leave a first-hand record of youth, including more about Tolkien’s circle, surely it would be a professional writer. Research on childhoods a century ago can be rather like trawling for coelocanths: you cast the net wide and once in a blue moon you haul in something really valuable. Finding living relatives may be the key, so I set my sights on Bonner’s.

I turned to Edinburgh Napier University, which now runs a campus on the old Craiglockhart hospital site. Librarian Catherine Walker could find nothing further about Bonner. As to the magazine, Napier only had scans of the extant issues, and she said: ‘If I ever find the missing issues, or issues from an original set of Hydra for our collection at Craiglockhart, then I can retire a very happy librarian.’

On the trail of Bonner, many sporadic hours of sleuthing, mostly online and in the British Library, revealed a literate and eloquent figure who was born in 1895 but swam against the tide of modernity. School records show he was interested in supernatural fiction and in Swinburne, and in debates ‘never fails to convulse the House’. He came up to Magdalen in Michaelmas 1914 but almost immediately enlisted in Kitchener’s Army, ending up in an anti-aircraft battery until invalided home in late 1916 with neurasthenia – shell shock, or as we call it today, post-traumatic stress disorder.

George Henry Bonner was at school with Tolkien in Birmingham before going to Oxford and on to war service

Treatment at Craiglockhart ran from November 1917 to March 1918 (where in one Hydra editorial he noted that ‘the exigencies of the service have taken from us Mr Sassoon’). Bonner himself wrote poetry: a sonnet appeared in the Basil Blackwell anthology Oxford Poetry 1920, alongside the work of Robert Graves and Edmund Blunden, edited by Vera Brittain and others. He had briefly returned to Magdalen, presumably to take a shortened degree, and was said to have gone on to Fleet Street. I found book reviews in the Occult Review and various essays in The Nineteenth Century, notably a series in which he made ‘The Case against “Evolution”’. However, I could find no journalism by him later than 1928, no trace of his fate, and no clue as to family.

Even after Tolkien and the Great War came out in 2003 the question still nagged at me, and I tried another tack: exploring his family tree in hopes of finding someone with traceable descendants. His only sibling, an observer in the Royal Flying Corps, had died over Northern France ‘in an attack by five enemy machines’ in 1917, 20 years old and unmarried. I could find no cousins, and gave up the attempt.

The breakthrough, so sudden it felt almost miraculous, came just after I moved from London to Oxford in 2009. I decided it was time to pick up several old threads of research, as I mentioned to my friend Peter Gilliver, an associate editor at the Oxford English Dictionary. ‘For a start, there’s this chap Bonner…’ I said.

The words were hardly out of my mouth before Peter responded, ‘Not Bonner whose wife used to work at the Dictionary?’ He mentioned a first name which sounded familiar, but it was not George, and anyway Peter’s Dictionary colleague surely could not have married anyone born in 1895. However, my notes confirmed that George Bonner’s younger brother had gone by the very name Peter had mentioned. That there was no connection between the Bonner brothers of Birmingham and this Oxford acquaintance of Peter’s seemed unlikely.

Excited, I dialled the Oxford number Peter had given me, and a polite voice confirmed that I had found the son of George Henry Bonner. Might I call on him to show him my research and talk about his father, I asked. By all means, he said.

And gave me an address just three minutes’ walk from my flat.

I showed Mr Bonner my notes. He showed me family photographs, and explained that his father had named him in memory of the brother killed in the war; but that he had died in 1929. He did indeed have some of his papers, and a few days later he fetched them down.

It all seemed too good to be true, and I immediately saw I had been right to rein in my hopes of a Tolkien-related breakthrough. There were plenty of articles, poems, even a play; but nothing personal – no diaries or letters, nothing whatsoever from school or referring to it or to his former school friends.

What really caught my eye were issues of the Hydra, with George Bonner’s name in pencil. At home I checked the issue numbers. And so I was able to tell his son that he had two of the three missing issues. We talked about what he could do with them, and I told him I knew they would be greatly welcomed at Oxford and at Edinburgh Napier.

Last summer he handed most of his father’s papers over to Magdalen College, where he had also been an undergraduate. I went to look over the Hydra issues with Dr Stuart Lee, director of the First World War Poetry Digital Archive. They provide a fascinating glimpse into a lost world, in which traumatised officers understandably fell back on the comfortable certainties of life as they had known it before the war. The Hydra reads like a school or college magazine, and reports enthusiastically, and often with gentle wit, on the clubs and pastimes fostered by the hospital inmates: debates, literature, poultry-keeping, sports, model boats, photography and gardening.

Dr Lee said: ‘This is a stunning discovery. It was long assumed that these editions would never resurface but to have access to them again after nearly 100 years is immensely useful to adding to our understanding of life at Craiglockhart.’

Ben Taylor, archives assistant at Magdalen, called the rediscovered Hydra issues ‘the jewels in the crown’ of the Bonner papers, which he has now catalogued. ‘It’s hugely exciting when lost treasures turn up like that, and wonderful to think that there will always be incredible “lost” documents waiting in attics and filing cabinets to shine brilliant new lights on things,’ he said.

‘They contain light-hearted prose, satire, poetry and artwork by many other young men, otherwise unknown to history. The magazines give vivid voice to their everyday preoccupations and frustrations, their worries, hopes, beliefs and disillusionments.

Mr Taylor added: ‘Bonner’s other papers give another layer of intimacy to this picture. He wrote a number of poems while at Craiglockhart, most of which were never published. In “Twilight” Bonner writes of the dread that comes to him with nightfall. “Let Us Taste Of The Joy Of Battle”, one of Bonner’s most vivid pieces, recounts the mental breakdown of a young infantry officer. I felt genuinely privileged to be allowed the hints and glimpses of Bonner’s inner life which these papers contain. From his efforts to be published, it is clear that he wanted very much to be read.’

[Added 2 July 2014: The Magdalen archivists have now highlighted the acquisition as ‘Treasure of the Month’ on the college’s blog, including lines from ‘Let Us Taste Of The Joy Of Battle’ and other Bonner writings.]

George Bonner’s son has no desire for the limelight, so I’ve kept his full name out of this piece. But his act of generosity did not end with Oxford. He also had doubles of some issues, and has donated these to the archive at Napier. Catherine Walker was delighted when I broke the news to her. Although she had retired as campus library manager just a week earlier, she remains curator of the archive. ‘You have managed to leave me speechless – no easy feat,’ she replied. ‘I would imagine that you can see my smile from wherever you are, as I can’t quite believe what I have read.’

Even though it turned up nothing about Tolkien, it is indeed astonishing, and feels hugely rewarding, that one small tangent of my research has reunited the missing Hydra issues with their home. And perhaps somewhere, in another attic or cupboard, the very last missing issue still waits to be rediscovered.

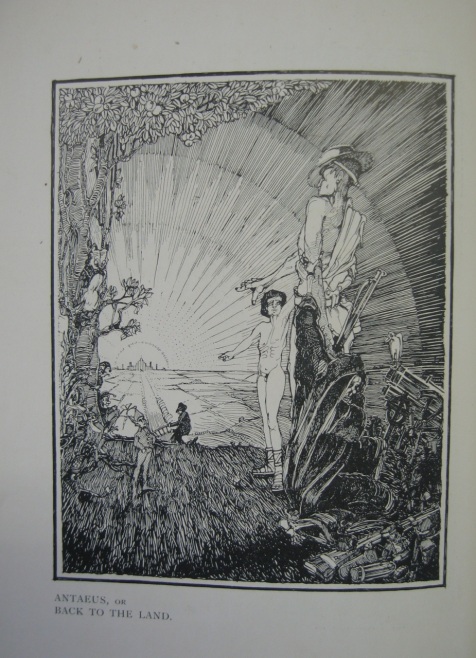

In Bonner’s Hydra editorial for January 1918, he writes: ‘Our late Editor, Mr Owen, has reduced the Antaeus saga to blank verse. This poem we hope to print in our next number.’ The poem does not appear in the newly-found issues, and perhaps was never published in Owen’s lifetime. But Owen did write an article in the January 1918 issue of The Hydra about the Greek myth of Antaeus, saying: ‘Now surely every officer who comes to Craiglockhart recognises that, in a way, he is himself Antaeus who has been taken from his Mother Earth and well-nigh crushed to death by the war giant or military machine . . . Antaeus typifies the occupation cure at Craiglockhart. His story is the justification of our activities.’

The article seems to have prompted the idea for a competition for the best picture inspired by the Greek myth. The illustration above was the winner of a competition at the hospital and is simply credited to a ‘Mr Robertson’. In his February editorial, Bonner writes: ‘Treating the legend in a somewhat unconventional manner, Mr Robertson shows us the youth Antaeus leading back into the green paths of nature the tired warrior at whose soul the horrors of darkness still clutch. Round his feet wood fairies and brownies dance, while beyond in the sunrise, there stretches through quiet ploughlands the path to the Golden City.’

This article, appearing here in a slightly modified form, was first published in Oxfordshire Limited Edition, the magazine of the Oxford Times, on 12 June 2014. The quotation from the 27 April 1913 letter from R.Q. Gilson to J.R.R. Tolkien is reproduced courtesy of the Tolkien Trust. Images from the Hydra are reproduced courtesy of The President and Fellows of Magdalen College, Oxford.

Pingback: Why World War One Is at the heart of Lord of the Rings | John Garth

Pingback: George Henry Bonner – so much more than a casualty of War | The Iron Room

Pingback: A friend of Tolkien’s TCBS tells a neglected truth of war | John Garth

Pingback: When History Delivers Tragedies: Wilfred Owen and WW1 | Maine Musing