As the Commonwealth War Graves Commission marks its centenary, I recall a 2014 visit to Flanders and northern France when I spoke to the gardeners who keep the cemeteries pristine.

With its postcards of poppies and memorials, its hotels and restaurants, its chocolateries and its 1914–18 bookshops, Ypres is proof that war is good for business. The Menin Gate stands uneasily on the edge of it all, its stone and its lawns immaculately maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here, the Last Post can provide a moment of reflection – so long as you ignore the iPads raised to film it.

If the missing whom it commemorates could rise again, would they (in the words of Siegfried Sassoon) ‘deride this sepulchre of crime’? Or would they feel the Menin Gate’s austere dignity is better than the triumphal monuments of previous wars – better than no memorial at all?

The manicured war cemeteries beg the same questions. The war writer Edmund Blunden felt such peaceful landscapes in France and Flanders ‘would have appeared sheer fantasy’ to the trench soldier. So who is all this meticulous planting and maintenance for?

The Commission’s gardeners take different views. Asked whether the dead care, Mark Heaysman, 54, says: ‘I think they do. In a way you’re giving them a service.’

Retired colleague Billy Jones, 65, is practical. ‘It’s for the families, the living. They can come here and look at the grave; it’s a beautiful setting. Can you imagine if you come, the headstone’s dirty, the grass is up to your kneecap and there’s no plants there, only weeds?’

The cemeteries would surely have consoled those who lost loved ones in the Great War. Seeking out the Somme grave of Robert Quilter Gilson (friend to JRR Tolkien in his ‘TCBS’ fellowship) his sweetheart Estelle King wrote to the Gilson family in 1919 about the small battlefield cemetery of wooden crosses she found:

‘They are going to put up marble stones, for which I am sorry but I expect it is best.

‘There will then be 18 inches for flowers and the grave will be covered with grass. I am asking to have a rose tree put, because I think it may last, and there is a young Englishman here who has said he will see to it. I think it will not make it conspicuous. It is just what I like. So quiet in a little less desolate part of this poor torn country.’

She also noted: ‘One or two graves were dressed up and somehow I resented it. Or no – felt it a pity.’ She was expressing an egalitarian view which was quickly becoming a matter of policy, and one today’s gardeners back to the hilt.

Previously, wealthier families would have had their own dead brought home for burial, leaving the rest dotted among overseas civilian plots going to seed. But the Commission has treated all graves with equal honour, regardless of rank. The focus falls on the man, lying where he died alongside those who died beside him.

The same principle of equal treatment applies on national, religious and cultural differences. Though much of the planting is in the style of an English country garden, this is not ‘some corner of a foreign field that is forever England’, in Rupert Brooke’s famous words: it is British and Commonwealth, and maple may be planted where significant numbers of Canadians are buried, or hebe for the ANZACs.

The same principle of equal treatment applies on national, religious and cultural differences. Though much of the planting is in the style of an English country garden, this is not ‘some corner of a foreign field that is forever England’, in Rupert Brooke’s famous words: it is British and Commonwealth, and maple may be planted where significant numbers of Canadians are buried, or hebe for the ANZACs.

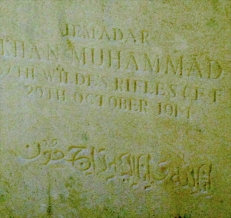

At Bedford House Cemetery near Ypres, I am shown a line of headstones with Arabic or Hindi inscriptions, commemorating men from India. At Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery in France, small white stones have been placed on one headstone by Jewish custom. Until the time comes to spray against lichen and algae, these will stay unless they are discolouring the headstone.

In all the cemeteries, a general sequence of plant types repeats every fourth headstone. It includes eyecatching ‘spot plants’ such as roses. Low ‘splash plants’ such as phlox and campanula protect from mud spatters but do not obscure the inscriptions. Seasonal plantings ensure colour most of the year. Despite their symbolism, poppies – which propagate wildly – are not included.

Gardeners discourage DIY plantings. ‘If somebody puts in a plant, we’ll try and leave that plant as long as possible,’ says Billy Jones. ‘But some people will come and try and plant an oak tree in front of an headstone – we do have to remove that!’

The equality of care may be the key to why the cemeteries draw reverence from military families and pacifists alike. ‘Still the British clip and mow and prune as assiduously as if the cemeteries were the palace gardens themselves,’ architect Paul Shepheard has written. ‘If you have ever wondered how it is possible to commemorate the dead without glorifying the war, they have discovered it.’

The equality of care may be the key to why the cemeteries draw reverence from military families and pacifists alike. ‘Still the British clip and mow and prune as assiduously as if the cemeteries were the palace gardens themselves,’ architect Paul Shepheard has written. ‘If you have ever wondered how it is possible to commemorate the dead without glorifying the war, they have discovered it.’

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, set up early in the war by a Red Cross unit commander and given a royal charter in 1917, now maintains 23,000 cemeteries or memorials across 153 countries. They include Brookwood in Surrey, where men who died of wounds in London hospitals would be sent on the midnight train so the public would not see. The latest is at Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) in France, built for 250 British and Australian dead whose remains were only discovered in 2009. In all, 1.7million servicemen and women from both world wars are interred in its cemeteries or commemorated on its monuments.

When I point out that their job does not seem especially cheery, the gardeners laugh. ‘Well, are we miserable?’ says Billy Jones. Does he ever try to visualise what it was like for the soldiers? ‘Yes, when it’s raining very hard.’ But it is a joke with a serious undertone. ‘What they talked about was mud – standing on duckboards because if you stepped off them you’d drown in the mud.’

When I point out that their job does not seem especially cheery, the gardeners laugh. ‘Well, are we miserable?’ says Billy Jones. Does he ever try to visualise what it was like for the soldiers? ‘Yes, when it’s raining very hard.’ But it is a joke with a serious undertone. ‘What they talked about was mud – standing on duckboards because if you stepped off them you’d drown in the mud.’

At Berks Extension Cemetery near Messines, site of a colossal battle in 1917, gardener Hugh Stewart recalls arriving from Dunbar at 22, half a lifetime ago: ‘There were 11,000 dead in the first cemetery where I worked, and some of them were a lot younger than me – 15 or 16 years old. It was moving, and I was quite shocked. You get used to it.’

The men six feet beneath might have understood. High standards and esprit de corps are the key for gardeners, as for many soldiers. Doug Sainsbury, 54, started his career gardening Wirral recreation grounds, and would sometimes be seconded to clean up civilian cemeteries. ‘That’s the last thing I’d want to do,’ he says.

‘But this is a high horticultural standard, very efficiently and professionally maintained. I’m part of 900 gardeners on the War Graves Commission worldwide. Nobody else in the world has a gardening crew like that these days. Is there anything depressing about this site? At the end of the day you look over the gate and you think, “Wow! It was worth coming.”’

Tyne Cot near Ypres takes the breath away. Within a horseshoe perimeter wall inscribed with the names of men with no known grave, the white gravestones extend seemingly forever. There are 12,000, including more than 8,300 marking bodies never identified. This, the Commission’s biggest single cemetery, is an iconic site.

Tyne Cot near Ypres takes the breath away. Within a horseshoe perimeter wall inscribed with the names of men with no known grave, the white gravestones extend seemingly forever. There are 12,000, including more than 8,300 marking bodies never identified. This, the Commission’s biggest single cemetery, is an iconic site.

In fact, that is its official designation, determining the amount of attention it must get. A team works all year round to keep the grass mown, borders edged, flowers flourishing. Pascal Wostyn, the Belgian in charge, has to factor in interruptions from regular ceremonies, from the bigger centenary events, and from filming, as well as from new interments. The gardeners – the real public relations face of the Commission – also field regular questions about the six VCs buried here.

For the Great War centenary, the number of ‘iconic sites’ is growing – even while the number of gardeners is falling. Doug Sainsbury is uneasy about this official ranking of cemeteries. ‘It’s a bit strange for me because all my career has been spent on giving everybody the same treatment.’

Of the sites we visit, Gourock Trench Cemetery near Arras is most likely to suffer. The small walled plot in the middle of an industrial area has 44 graves. Somehow the mobile team of gardeners responsible for this and other sites will have to keep up standards while time and funds are diverted towards the big iconic ones.

Of the sites we visit, Gourock Trench Cemetery near Arras is most likely to suffer. The small walled plot in the middle of an industrial area has 44 graves. Somehow the mobile team of gardeners responsible for this and other sites will have to keep up standards while time and funds are diverted towards the big iconic ones.

American and German policies on burial avoided such problems: both would remove their dead from battlefield sites to gather them in big, concentrated cemeteries. But this stretches or severs the link with the battlesite – such a powerful trigger for deep reflection by visitors to the Commonwealth graves.

***

For bikers, it’s motorcycle marques. For the gardeners of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, it’s lawnmowers. The brand names John Deere, Husqvarna, Honda and Walker trip off their tongues. Likewise the various chemical treatments against insect and lichen. They compare the rose species with even deeper passion: Super Trouper, Rotilia, Trumpeter, Fellowship.

At Bedford House Cemetery, recently retired Billy Jones shows off the system which uses largely natural processes to create compost for all the Belgian sites and incidentally feeds a small on-site lake teeming with fish and other life. ‘For the frogs this is like the Hilton Hotel,’ he says.

The gardeners face perennial challenges. The Belgian rain and the clay soil are the same combination that put a curse on Passchendaele. The biggest cemeteries, Tyne Cot and Lijssenthoek, are located precisely where the soil is wettest – a telling sign of the fatal role played by the mud in the First World War. The gardeners’ work can be impossible when the borders flood.

At least here bones do not tend to emerge from the ground, which they sometimes do in sandier coastal areas. ‘Mostly soldiers are buried deep – in blankets tied with wire, though the Canadians and Americans had coffin burials,’ says Billy Jones.

Alarmingly, live munitions are still found on the old battlefields – and therefore also in the cemeteries, especially during periodic re-levellings of the ground. At Bedford House the composter had a close encounter, as Billy recalls. ‘He’s got a machine that actually shreds the soil – hammers it. What came flying out? A hand grenade.’ At least if the British Mills bomb had exploded, its fragments would not have penetrated the machine’s thick metal.

A shell might have been a different matter. ‘If you see the head still on a shell, run in the opposite direction,’ says Billy, an ex-Army man. He tells how two construction workers were killed and two more injured in Ypres when a First World War shell exploded in March. Rumour has it they had been hammering at it to salvage the brass. Mercifully for the other workers – and for the neighbours – it was not mustard gas.

A shell might have been a different matter. ‘If you see the head still on a shell, run in the opposite direction,’ says Billy, an ex-Army man. He tells how two construction workers were killed and two more injured in Ypres when a First World War shell exploded in March. Rumour has it they had been hammering at it to salvage the brass. Mercifully for the other workers – and for the neighbours – it was not mustard gas.

Billy tells of one tourist who found a battlefield shell, put it in his suitcase and went to carry it onto the Eurostar, where it was caught in the X-ray. It was still primed. ‘A lot of civilian people think, “It’s a shell, it’s old, it won’t explode,’ he says. ‘But even a hundred years later, they will go off.’

No gardeners have been injured by explosives. Infrequently, there have been falls from the backs of van and fingers caught in mole traps, but the Commission seems responsive.

One recurrent challenge for gardeners used to be that the Commission would transfer them to another site, perhaps in another country, with just six weeks’ notice. It was like being in the military, except the Commission provided no housing and little help with reorientation.

Derek Richardson, who arrived from Dublin with his wife, spent three years in Belgium, eleven in France, then nine in Germany, and has now been back in Belgium for three years. He says: ‘Sometimes you’re quite happy where you are. If it’s a change of country, it’s a big change – language, culture, education for your children, et cetera.’ Billy Jones puts in: ‘I think we had a higher divorce rate than the Army.’ Now only those who apply are relocated.

Under the current drive for efficiency, the big issue for the gardeners is stress. Innovations such as mulching – where the mowers leave the cut grass lying rather than taking it away – may not save the time promised by managers. Meanwhile staff numbers are being allowed to fall, with no one replacing gardeners who leave, and no extra hands in emergencies anymore. When I see a mower in action, I am astonished: he could qualify for Le Mans.

Under the current drive for efficiency, the big issue for the gardeners is stress. Innovations such as mulching – where the mowers leave the cut grass lying rather than taking it away – may not save the time promised by managers. Meanwhile staff numbers are being allowed to fall, with no one replacing gardeners who leave, and no extra hands in emergencies anymore. When I see a mower in action, I am astonished: he could qualify for Le Mans.

Visitors rarely see mowing in progress, and the cemeteries seem to be kept pristine by magic. The illusion is down to the sheer scale of the job. One mobile team of 12 (previously 14) may have to maintain more than 60 sites, and speed is essential. ‘It’s carefully calculated,’ says Doug Sainsbury. ‘We go there for a purpose, we complete it and then we move on to the next site.’

The original workforce included many demobbed soldiers who saw a purpose in honouring their fallen comrades, and most were British. Sons would follow them into the profession.

But now Britons are a dwindling minority. When they leave they are replaced by locals recruited straight from school, factory or dole. ‘Gardening in Belgium tends to be low-rated,’ says Mark.

A bigger issue is raised by Chris Kaufman, former Unite national secretary for agricultural workers. ‘The gardeners are not just horticulturalists – they are social workers, because people come to the cemeteries and they are suddenly hit by the enormity of it all. They come to find their old relations and they suddenly find they were 17 years old when they were killed.’

It’s a down-to-earth variation on a theme voiced by Rudyard Kipling – the man who advised the Commission on its headstone inscriptions – in a story called ‘The Gardener’, in which the man seen tending the graves at the end is clearly meant to be understood as Christ. The gardeners have always stood for far more than the practical sum of their work.

As Chris Kaufman points out, even while the numbers of British gardeners fall, visits from Britain to the cemeteries are increasing, thanks to the Channel Tunnel, programmes like Who Do You Think You Are? and the war centenary.

Will the work and workforce be reduced and the cemeteries run down after 2018? That is an anxiety. But the gardeners are confident the Commission’s work will go on, even though the most recent figures put the annual cost above £55million – more than three quarters of it from the British Treasury.

As Mark Heaysman says, ‘Which government is going to turn round and say, “We’re not going to look after the war dead anymore”?’

All photographs © John Garth. Lines from a letter from Estelle King are reproduced with permission of Julia Margretts. This is an edited version of an article written for Unite the Union, and is also reproduced by permission.

Thank you, John. Fascinating.

Two of my mother’s uncles are buried in war cemeteries on the Western Front. It comforts me when I read the way in which the gardeners (spiritual descendents of Sam Gamgee?) speak. The comfort is like an arm about my shoulders and a voice (the voice is grandfatherly) saying, “Don’t worry lad. It’s all right.”

Thank you, indeed! What a fine article, answering so well things it had not yet occurred to me to ask.

Something very interesting I just learned about are the bells of St.George’s, Ypres. The Church was intended to have bells when it was built, but has gone since 1929 without them. Now, bells have been cast, inscribed with the names of bell ringers who lost their lives in the war, and will be blessed by the Bishop of Gibraltar in Europe on 22 October, becoming the only set of change ringing bells in Belgium, I believe (and in Europe?), with English bell ringers in residence for some time to train up local Belgian ones. The Church’s website has a number of vividly illustrated posts tracing the progress of the undertaking.

Lots of good detail in the Bishop’s blogpost!:

And, through the kind offices of Amy Harris who made the reports, and the Rev. Gillian Trinder, who brought them to my attention, some lively visible and audible first impressions, reactions, and further background:

Thank you, David. That’s a touching thought. I do hope the neighbours like them!

Thank you! The BBC continues, and varies, the theme, with a glimpse of future plans: “Bell ringers to mark 100 years since the end of First World War”!:

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-41957521